EDITOR’S NOTE: Michael McWalter, former Director, Petroleum Division and Adviser to the Government of Papua New Guinea, and erstwhile petroleum adviser to the governments of Ghana, Liberia, Cambodia, São Tomé, and South Sudan, recalls the foundations of petroleum resource development in Papua New Guinea, and continues his story of oil and gas exploration and production in independent Papua New Guinea.

Michael McWalter is a certified petroleum geologist and technical specialist in upstream petroleum industry regulation, administration and institutional development.

Introduction

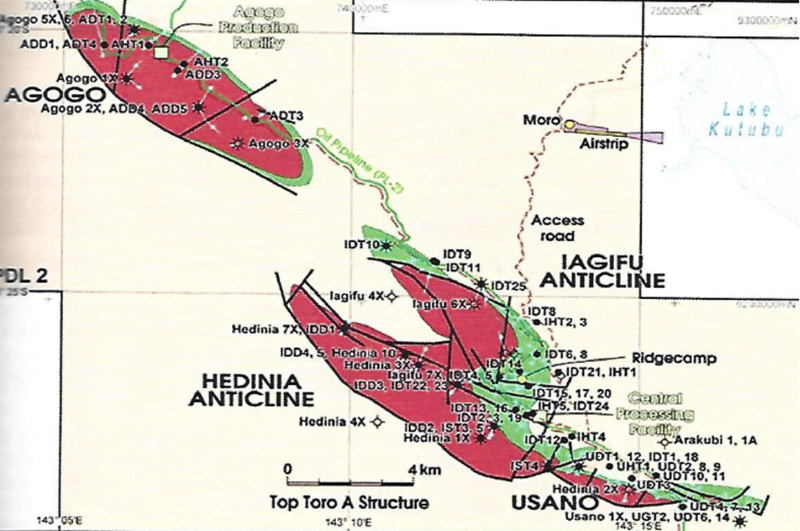

In my last article titled “Decades of Exploration to First Oil and Gas Production,” I told the story of the early days of petroleum exploration in the new nation of Papua New Guinea up to the days of first oil and gas production in the early 1990s. Gas was first produced and sold from the Hides gas field by BP and Oil Search in December 1991, and crude oil was first produced and sold from the Kutubu fields by Chevron and their joint venture partners in June 1992. The discovery of crude oil and natural gas at Iagifu and Hides respectively in 1986 and 1987 in significantly large accumulations worthy of commercial production sparked an exploration boom in subsequent years.

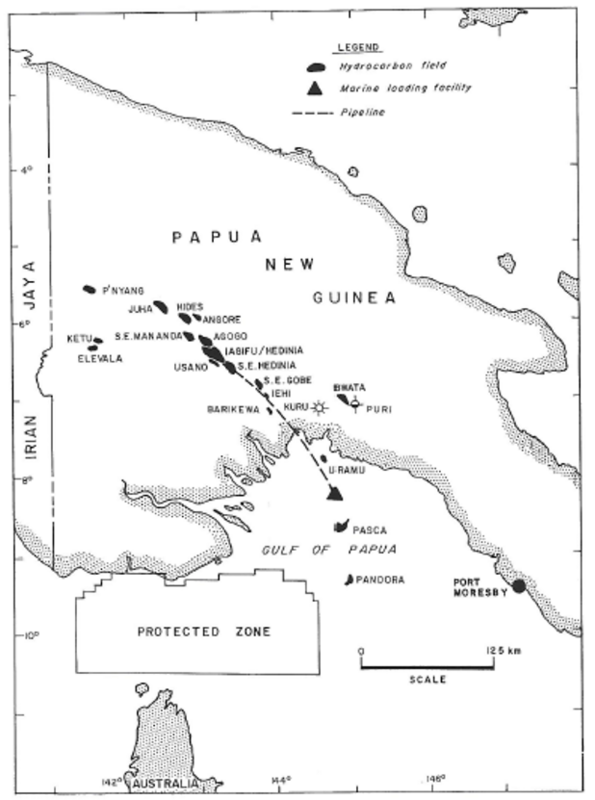

Papua New Guinea became a vogue place for oilmen to be. In the 20 years or so after these discoveries, Port Moresby was home to oil and gas companies large and small that needed to be in this opening frontier of exploration; such is the herd mentality of oilmen. Together they spent a staggering 3 billion kina, which amounted to some US$2 billion at the exchange rates of those days, or about US$4.1 billion in today’s money. That effort involved the drilling of some 150 wells and the conduct of some 108 seismic surveys that eventually led to the discovery of moveable hydrocarbons in 61 wells and the location of 20 new petroleum accumulation fields, though many of these contained natural gas rather than oil. I now continue the story. However, it is an immense tale, so I shall just delve into it here and there to show where the petroleum industry has taken us at the time of our 50th anniversary of independence. And I apologise if at times my tale is anecdotal or lacking.

Gobe and Moran Oil Fields

Along the frontal trend of anticlines in the Papua New Guinea fold and thrust belt, wells drilled on the Gobe and Moran structures found additional pools of oil, in lesser quantities than the accumulations of the Kutubu fields, but still enough to warrant development. Almost every anticline was drilled along the frontal trend, even to the point of one supposed anticline turning out upon drilling to be a syncline rather than an anticline, and thus unable to trap any fluids in the subsurface.

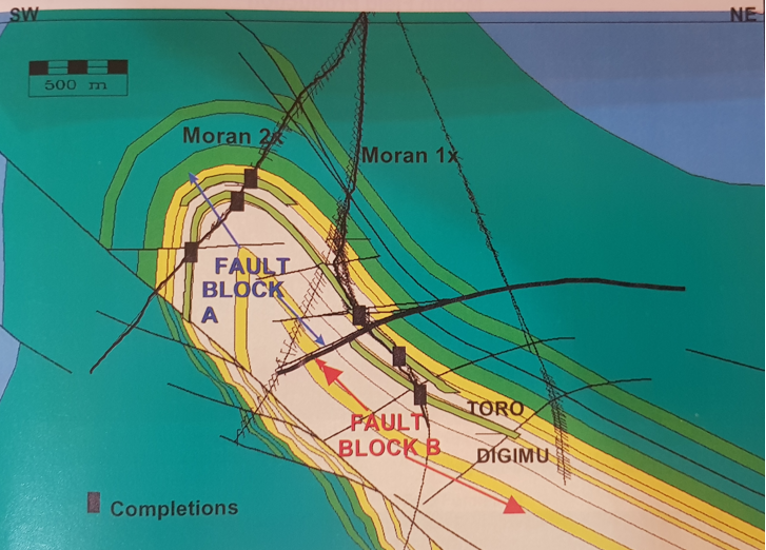

The Moran field north-west of Kutubu was estimated to hold about 113 million barrels of recoverable oil, whilst the Gobe field was estimated to contain about 83 million barrels of recoverable reserves. Both of these fields had structural complexities due to faults that compartmentalised the accumulation of oil within the reservoirs.

This isolation of separate pools of oil also led to some considerable rivalry between adjacent petroleum licensees, who sought to exert their prowess one over the other by naming the parts of the fields in their licences differently. Hence, we had supposed field names like South East Gobe, Gobe Main, Moran Central and North West Moran. With these fields awkwardly extending across licence boundaries, both co-ordinated development and unitised development arrangements had to be negotiated between the different licence joint venture groups. This was not always easy due to often intense corporate rivalries and differing economic and commercial positions.

The development of these fields ensued with different production arrangements. The Moran field depended on the use of the Kutubu Central Production Facility, to which flowlines from Moran to Kutubu were installed. Meantime, the Gobe field had a separate production facility installed (the Gobe Production Facility) and a short project-specific spur pipeline. Both of these fields used the Kutubu Export trunk oil pipeline and its integral offshore Kumul Marine Terminal for transmission and dispatch of crude oil for export. This entailed the negotiation of tariffs for the use of the various Kutubu facilities, which added further complexity to the commercial arrangements for field development. However, such arrangements did serve to optimise the use of existing field processing facilities, storage and transportation systems, and obviated the unnecessary and redundant duplication of petroleum infrastructure.

In the case of the use of the Kutubu Export Pipeline by the producers of the Moran Joint Venture and Gobe Joint Venture, some companies were also parties to the Kutubu Joint Venture, whilst others were not. Beguiling arguments for high tariffs were made by those members of the Kutubu Joint Venture that were not involved in these new field developments, while conversely equally beguiling arguments were made for low tariffs by those members of the Moran and Gobe Joint Ventures that were not involved in the Kutubu Joint Venture. Those involved in the new field developments as well as the Kutubu project were quite mute in their tariff arguments. The threat of impending ministerial regulation, as was then permitted by the Petroleum Act, rapidly crystallised the thinking of the various licence ventures, and those commercially adamant arguments rapidly dissolved into a commercial and fair resolution of the tariffs!

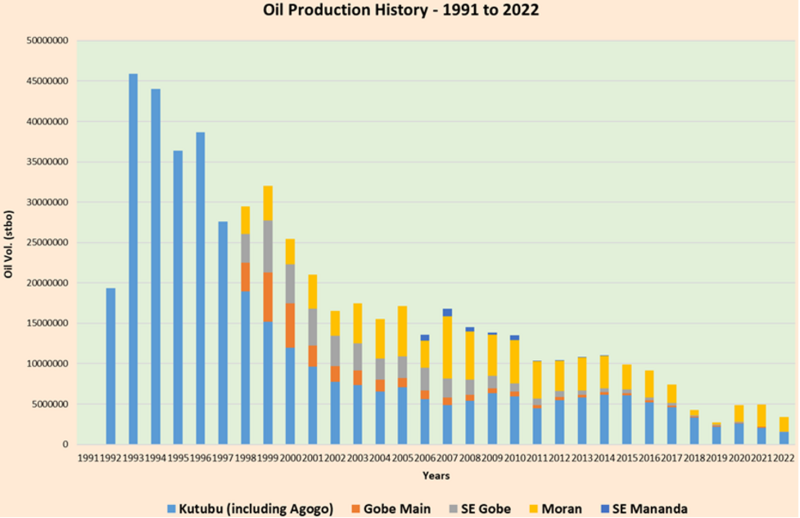

Oil Field Production

Both Gobe and Moran oil fields commenced production in 1998, some six years after the Kutubu field. Gobe reached peak production in 1999 at an annualised rate of 34,278 barrels of oil per day (bopd) and declined thereafter, whilst Moran only reached peak production in 2007 at an annualised rate of 21,503 bopd. The two fields contributed to supporting Papua New Guinea’s aggregate oil production as that at the Kutubu fields inexorably declined as reservoir energy was depleted.

The development of the Kutubu field has, in retrospect, been a great success, with oil production continuing to this day, albeit much reduced in volume from its high production rate of its halcyon days when it almost reached 150,000 barrels of oil per day, plus production of the field’s associated gas.

The Kutubu development was launched on the basis of recoverable oil reserves of just 164.8 million barrels, but as of 31 December 2019, it had produced 319.8 million barrels of oil. Based on an estimated original-oil-in-place volume of 556.2 million barrels, this suggests that the original projection of just 29% recovery has eventuated in as much as 57.5% recovery by the end of 2019. With production still taking place at about 3,000 barrels of oil per day, the Kutubu field is clearly reaching its last days. It does this in considerable glory as it reaches 60% recovery of its original oil-in-place, quite an extraordinary recovery factor.

Admittedly, associated gas obtained from the field separators was originally re-injected into the field at the gas/water interface as a semi-miscible flood so as to enhance oil recovery, but even by the standards of such secondary recovery techniques, this level of oil recovery has been quite remarkable. Of course, a large uncertainty always remains in the petroleum geology, insofar as we do not have precisely mapped subterranean field limits on account of it not being possible to obtain clear seismic imaging of the reservoirs. We therefore cannot rule out the possibility that oil is being extracted from an original pool that may have a geometric volume and areal extent somewhat different from that originally conjectured, which was based solely on well penetrations and geological mapping.

Whilst the Kutubu fields have been a great success, both Moran and Gobe fields have had a chequered development history with various problems of one kind or another. The development of the Gobe fields started with feuding over operatorship between the Chevron-led joint venture and the Barracuda-led venture. Barracuda, a subsidiary of Mount Isa Mines Ltd, had acquired the small independent company Command Petroleum, which had bravely drilled the South East Gobe-1 discovery well as operator of Petroleum Prospecting Licence No. 56. Chevron’s prowess won out, and they retained operatorship over the Gobe field development and subsequent production.

Intractable problems with customary landowner identification of the people of the Gobe area have persisted through development and production. The land of the Gobe Mountains was gazed upon by both people from the north and the south and only sparsely used for hunting and gathering and ancestral rights. The land was hotly contested, and ownership was very difficult to determine outright. The Government had to resort to using the Lands Title Commission to help determine landowner rights. With initial development delays, production never reached its planned output, only reaching 34,000 barrels of oil per day in September 1999. Additionally, reservoir problems were encountered which involved sanding problems due to the reservoir sandstone being extremely fragile and friable.

Extensive extended well testing (EWT) at Moran enabled early oil production and the gathering of some very useful field production data. However, it depleted the reservoir pressure to such an extent that the associated gas started to effervesce from the oil and create a gas cap above the oil. This required re-pressurisation of the Moran oil field using gas sourced from the adjacent Agogo field. The Moran oil field’s high compartmentalisation broke the field into many small fragments which were often difficult to resolve.

Gas Development Preparations

In the absence of any further significant oil discoveries, the future was considered to lie in the development of the gas fields, where exploration drilling was demonstrating them to be significantly more abundant than oil by a factor of about ten times.

The Government realised that its petroleum endowment was not so full of oil, but was comprised substantially of natural gas resources. It was recognised that it would be difficult to develop these in the absence of any domestic gas demand from households, commerce or industry, and all the more so because PNG is remote from the gas markets of other nations.

Accordingly, in 1992, the PNG Government, through the newly established Petroleum Branch of the Geological Survey, commissioned a special study on all the discovered oil and gas fields of PNG. This work was conducted by the US firm Scientific Software Intercom in collaboration with the Government’s Petroleum Division and sought to assess the extent of the petroleum resources and reserves to proper and systematic standards of reserve reporting as were then published by the Society of Petroleum Engineers.

Based on aggregation of the recoverable reserves, an economic study was then undertaken applying the then prevailing PNG petroleum fiscal and commercial regime. The results were presented to the National Executive Council, showing that if the gas fields discovered to date were aggregated, there could conceivably be a large-scale commercially viable gas development based on the export of liquefied natural gas (LNG) to energy-hungry East Asian markets. However, more work would be needed to obtain better estimates of the recoverable gas reserves, the quantification of gas field development costs and the construction costs of a gas conditioning plant, gas pipelines, liquefaction facilities, and storage and export facilities.

The Government liked the idea of gas development and embarked on reviewing and examining suitable policies for such and began fostering the notion of gas development. Economic and policy studies were conducted and extensive discussions between gas field licensees, owners and promoters ensued. After extensive consultations between Government agencies and licensees, in 1995, the Government tabled a Natural Gas Policy before the Papua New Guinea Parliament. The policy laid down the regulatory, commercial and fiscal terms that the Government was willing to consider for the encouragement of investment in gas development. Key features were the introduction of Petroleum Retention Licences (PRLs) to allow the companies to keep their discoveries beyond the period of tenure provided by a normal Petroleum Prospecting Licence. These would be allowed in consideration of an acceptable programme of gas field appraisal and delineation, the conduct of commercial studies and development promotion by the licensees. So long as a field was currently not commercially viable, the PRLs would allow retention by the licensees for up to 15 years, and no longer. This was a significant encouragement to the holders of petroleum prospecting licences, which normally only gave a combined tenure of eleven years in which to explore, make a discovery and launch a field development. The introduction of PRLs recognised the very long lead time for large-scale gas development.

The gas policy also introduced a single ring-fence for project development, including gas pipeline infrastructure, liquefaction plant and marine facilities. Based on considerable economic modelling and debate, the policy landed on a concept of 50/50 sharing of the net value between the developer and the Government. The income tax rate for gas operations was set at 30% of net profits, without any dividend or interest withholding taxes, and the State decided it would keep its right to take up to 22.5% equity in the entirety of any development, including the LNG plant and associated facilities. Royalty rates and development levies were left at 2% of the wellhead value. Fiscal stability was to be offered, but only upon payment of a 2% income tax premium and the execution of a Fiscal Stability Agreement with the Government. This was effectively an elegant user-pays principle. Standard depreciation allowances on capital expenditure and exploration would remain at 10% per annum and 25% respectively under the existing fiscal regime. These still represented a quite harsh depreciation schedule by petroleum sector standards because it is not possible to fully recoup one’s field development costs until ten years after expenditure, unlike more accelerated cost recoveries allowed in Production Sharing Contracts.

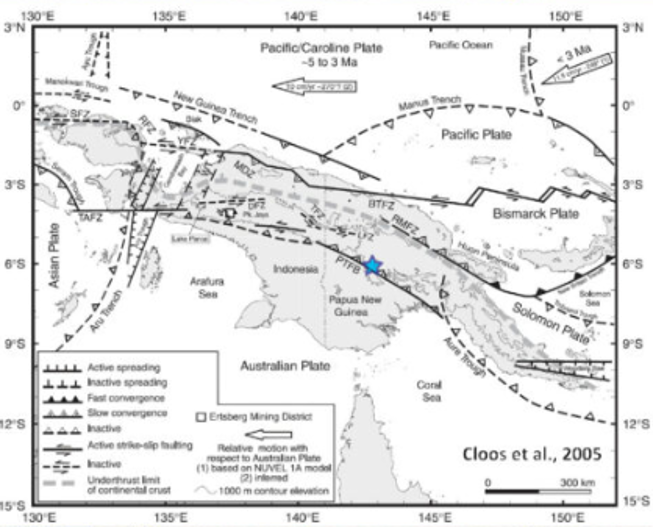

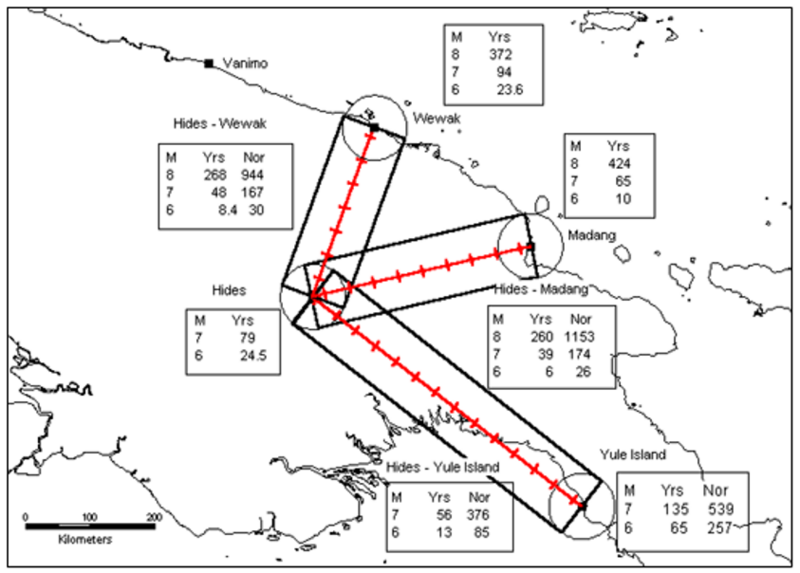

With the foundations for commercial gas development defined by the new gas regulatory and fiscal regime, Exxon and BP pursued their LNG development plans based on the large Hides gas field with the idea of taking the gas to the north coast of Papua New Guinea. There in Madang, they planned to build a coastally located deep-water liquefaction plant sited next to deep-water fjords which would give direct access for LNG carriers to moor alongside these coastal facilities. However, these plans faltered due to the Asian financial crisis in 1997 and the consequent sudden reduction in East Asian LNG demand. The tragic and terrible tsunami that occurred in 1998 at Aitape on the north coast accentuated the seismic risk for an LNG plant on the north coast of Papua New Guinea. The tsunami demonstrated that, whilst placing any LNG facilities nearer to markets, any north-coast-located LNG facility would have to be built to much more exacting standards of construction and operation to cater for the additional seismic risk.

The Petroleum Division, mindful of the seismic hazards of the northern part of PNG, had earlier commissioned a PNG Seismic Hazard Study from Dr Horst Letz, formerly resident seismologist at the Port Moresby Geophysical Observatory (and later to be the chief scientist who set up the Earthquake and Tsunami Warning Centre in Jakarta, Indonesia). This report was published around the time of the tsunami. It clearly defined the risk and indicated that a southern coast location for an LNG plant and facilities would be preferable, even if it meant a slightly longer shipping route for LNG carriers to transport LNG to likely markets in East Asia.

Additionally, gathering gas from gas fields aligned with the prevailing geological structure of the Papuan Basin running north-west to south-east would have a better chance of collecting gas from multiple fields to be found in the same orientation rather than orthogonally across the dividing range of mountains and across the swamps of the Sepik River basin, all of which were void of gas discoveries. Later, BP withdrew from Papua New Guinea and took their ideas about larger-scale gas development by way of an LNG project to West Papua in Indonesia, where they successfully launched the Tangguh LNG Project in a similar environment, peopled again by Melanesians.

When the amendments to the Petroleum Act were being prepared for gas development pursuant to the approved Gas Policy, the results of policy studies on landowner benefits (both royalty and equity sharing), strategic access to pipelines and petroleum processing facilities, and elementary domestic gas business provisions became available. An effort was made to incorporate them into the amendments to the Act. The Government was also intent on providing statutorily defined benefits to communities hosting any future oil and gas development, together with proper processes of consultation and liaison with communities, rather than having negotiated and often capricious benefit-sharing arrangements. For such benefits, the Government devised the idea of a separate Development Agreement between the community parties, sub-national Government parties and the State. The allocation of defined and additional benefits was to be agreed in a formally convened development forum. Proper professional research was also to be made as to land matters through the conduct of formal social mapping and landowner identification studies conducted by and at the expense of the petroleum licensees themselves, but with such studies being furnished to the Government for its use.

Significant and specific political lobbying arose from the Southern Highlands Province, home to many of the known major oil and gas fields. The Province, quite bizarrely, wanted a separate Gas Act just for gas operations. For a while, it seemed that the National Government was stymied in its plans for gas development due to these concerns, but extensive consultations took place. In the resulting compromise, the Government agreed at the political level to introduce some of the reforms suggested by the Province, but only if the Act would remain intact, though it was now agreed that the new Act would be rebranded as the Oil and Gas Act, whilst still generically referring to petroleum for the most part. Thus, the Oil and Gas Act, No. 49 of 1998, was born. It represented a major restatement and overhaul of the former Petroleum Act and has paved the way for improved and formalised participation by communities and their sharing in statutorily defined benefits arising from oil and gas production. It is only a shame that timely and efficient benefit processing and reconciliation with the correct beneficiaries have been difficult at times to achieve. Disputation of land ownership has not helped in this matter.

Gas to Australia Schemes

Meantime, Chevron, realising that they were handling increasing volumes of associated gas in their operation of the Kutubu oil fields (as much as 400 million standard cubic feet of gas per day (MMSCFD)), bought out the commercial notions that the International Petroleum Corporation (IPC) (the early Lundin Oil Company) had about developing their offshore Pandora gas field. Pandora had been discovered by IPC in 1988 in the middle of the Gulf of Papua, and subsequently the company had plans of producing and piping gas to Townsville in Queensland, Australia, to supply a 200-megawatt power plant. Chevron had gas aplenty and was taking great pains to re-inject as much of it as possible into the reservoirs, but if that gas could be sold into a market, they considered that perhaps that could enhance their sales revenue and obviate the need to inject quite so much gas.

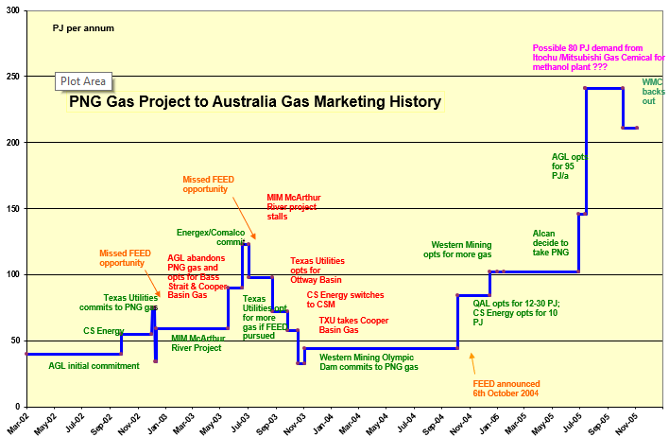

There then ensued a period when all manner of gas development notions were focused on transmitting gas to Australia from the associated gas of the producing oil fields plus gas from development of the as-yet-undeveloped gas fields, such as Hides, Angore, Juha and P’nyang. Over the course of the next several years, various schemes to send gas southwards to Australia waxed and waned and struggled to gain traction.

In the early 2000s, exploration reached an all-time low as corporate enthusiasm waned. There was little point in exploring for petroleum with the high likelihood of finding gas rather than oil, if even the substantial discovered gas fields could not be developed and produced. In 2003, Chevron departed the Kutubu Joint Venture as its material economic interest in the Kutubu Project diminished below its corporate threshold. It sold its Papua New Guinea assets and interests to Oil Search.

The PNG Gas Project, also known as the PNG Gas to Queensland Project, or Gas to Australia Project, ended up at one time with over 4,300 kilometres of trunk gas pipelines and laterals hanging off the Papua New Guinea gas fields with nearly 250 PJ per annum (equivalent to about 600 million standard cubic feet of gas per day at 1,056 British Thermal Units per cubic foot) of potential gas sales. Alas, fundamental flaws in the concept led to most of those potential customers being quite quixotic.

Most of that infrastructure was in the north-eastern quadrant of Australia and its installation was to be expensed against the supply of gas to a wide and quixotic range of Australian gas customers. With low gas prices, high steel prices and the emergence of coal seam methane development notions in Australia, it was eventually realised that PNG might end up giving its gas away for nothing, and that the only value for Papua New Guinea might remain in the natural gas condensates extracted from the gas in Papua New Guinea. The PNG Gas Project for the supply of gas to Australia failed. Additionally, such a large-scale transnational activity needed considerable support from the Governments of both Australia and Papua New Guinea to protect sovereign interests. Fundamentally, Australia’s policy of gas-versus-gas competition and gas system regulation was at odds with such a trunk gas delivery pipeline, which would need special treatment within the Australian pipeline regime and due respect for its transnational delivery of gas.

Eventually, in 2008, an abrupt turn was made to change all the development notions towards supplying gas to an LNG plant to be located on the Papuan coast beside the Gulf of Papua. An effort was immediately made to market the gas as LNG to East Asian markets. Australia had specifically encouraged gas-versus-gas competition, but in doing so it spoiled the market price for gas imports from countries such as PNG and encouraged the furtherance of coal seam methane (CSM) schemes to extract gas from extensive coal deposits in Queensland. Indeed, this later gave birth to Australian LNG export projects supplied by gas from CSM sources, the supply of which has not turned out to be so plentiful, necessitating the purchase of make-up gas from domestic markets and thus creating a domestic gas supply shortage along Australia’s east coast. In abandoning gas supply to Australia by pipeline, Papua New Guinea now needed to consider capturing the premium values that gas exports into energy-deficient East Asian economies were able to achieve.

The dependence on external infrastructure and specific gas demands in Australia was not seen as either politically attractive or sustainable, nor was it commercially attractive due to low gas prices brought about by Australia’s gas competition policies. It was most fortunate that Papua New Guinea backed away from such schemes for the dispatch of gas to Australia. Thus was born the PNG LNG project.

PNG LNG had many factors in its favour as a distinct source for LNG for supply to East Asian markets. PNG is a non-aligned Christian nation; it is not an Islamic nation. PNG was desirous of investment and keen for development based on commercial fiscal terms. PNG, as a nation, has open-ocean access and does not rely on any strategic straits. It has a Westminster-style Government and observes the principles of law and contract. PNG is favourably positioned to supply the Australasian region, but can reach out to serve Asian, Pacific and American markets. With diminishing oil production and the absence of new oil finds, PNG’s explorers needed to capitalise on prior exploration investments that failed to find oil. Gas in the new 21st century was no longer a hindrance and could be profitably developed, even extending the life of the oil fields.

The PNG LNG project was projected to export LNG at a heating value of 1,135 BTU/SCF gas and the liquids were forecast to sell at US$60/barrel. Anticipated LNG prices were: US$8.07 per MSCF, equivalent to US$10.20 per MMBTU, or US$9.69/GJ. The original plant design was upgraded early on from 6.3 million tonnes LNG per annum to 6.9 million tonnes LNG per annum for production over a 30-year period. Gross income was estimated to be about US$74.3 billion. Even at US$50/barrel oil, the project was still forecast to yield US$61.9 billion in LNG sales. The gas is rich in natural gas liquids (NGLs), so at just 20 barrels of NGLs per million cubic feet of gas, some 210 million barrels of NGLs were forecast to yield an additional US$12 billion of sales revenue.

In May 2014, PNG became an LNG exporter and is now producing consistently more than 8 million tonnes per annum (mta) LNG to customers in China, Japan and Taiwan – well above the nameplate capacity of the original LNG plant design. It got there because of fine operatorship on the part of ExxonMobil of a coherent joint venture. ExxonMobil was able to market the gas to top-quality customers and obtain superior project financing. The only major disappointment has been the collapse in crude oil prices below projections on several occasions, and hence the LNG prices due to the indexing with crude oil. For the first year, some elevated prices were obtained, but clearly the fall of crude oil below US$30 per barrel in the early days of LNG production hurt the project economics and outcomes to all stakeholders, as it again did during COVID-19 when LNG prices plummeted below US$3 per million British Thermal Units.

The PNG LNG Project produces gas from a variety of gas fields including the Hides and Angore gas fields, and the Kutubu, Moran, Agogo and Gobe oil fields. The more remote Juha gas field is set to produce gas later. Altogether, these fields have about 9 trillion standard cubic feet (TCF) of gas to contribute for liquefaction.

Other discovered gas fields will likely be developed later and, despite being cast as different projects, will likely seek to optimise gas infrastructure; these are the P’nyang gas field and the Muruk gas field which can add about 5.25 TCF of additional gas for liquefaction. Quite how much gas will eventually be recovered from each field still has considerable uncertainty, just as stated before for oil recovery. This is due to the considerable remaining uncertainty of definition of the subsurface reservoir volume due to a lack of seismic imaging and lateral resolution of field boundaries. The geology is already complicated on account of the extensively folded and faulted nature of the strata, so we might anticipate some surprises, both positive and negative.

Access to lands for the PNG LNG Project development came with resounding landowner consent after enormous development forums were held at project level in Kokopo in New Britain and at licence level in each licence area. During the forums, the sharing of the benefit streams of the 2% royalty, 2% free equity from the State, 2% development levy, and other project grants including business development and infrastructure grants were discussed. Oddly, whilst some grants were paid quite promptly, distribution of the royalties and equity benefits has been the subject of considerable delay, mainly due to some remaining uncertainties about landownership, often brought about by disputes over landownership. This is exceedingly difficult to accomplish where traditional customary title persists, often with multiple and overlapping ownership and usufructuary rights. But notwithstanding this situation, the landowners have been extremely patient, and in some cases, and for many years into LNG production and export, they have remained quite stoical.

Aside from the statutorily defined equity benefit of 2% of the project, the Government agreed to provide additional equity to the communities in the amount of 4.2%. This was promised to them in the main PNG LNG Project development forum in Kokopo. This was to have been a commercial deal, but successively its commercial cost to the beneficiaries has been whittled down to nothing. Provided that this additional equity benefit can be managed properly and in accordance with the Oil and Gas Act, it will be a most valuable asset once the project finance has been paid down by the State.

Elk/Antelope Gas Field

A bold and entrepreneurial company called InterOil, championed by a charismatic leader Phil Mulacek, had two Petroleum Prospecting Licences (PPLs) in the Eastern Papua Fold Belt: PPLs 237 and 238. They were granted in 2003 near to small historic gas discoveries of the 1950s, such as Kuru, Puri and Bwata, each in Miocene limestones.

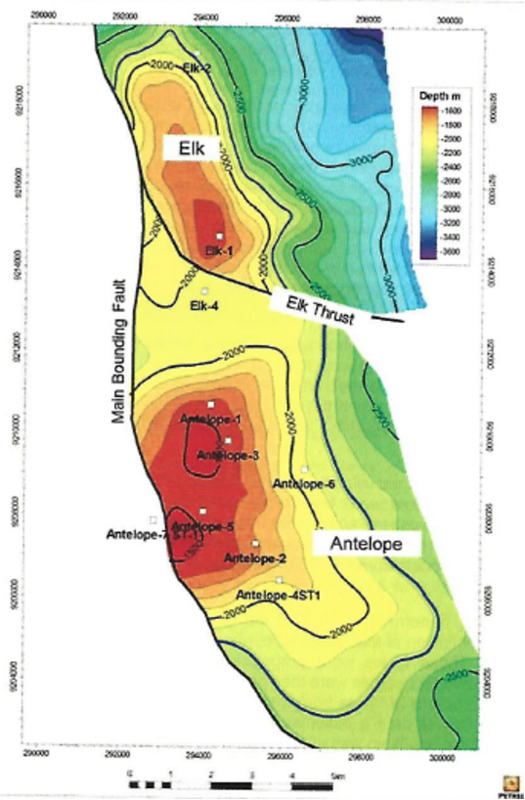

In 2006, the Elk-1 well was drilled and declared to be a gas discovery in fractured Puri Limestone after testing at 21.7 MMSCFD. Two more wells, Elk-2 and Elk-4, were drilled to appraise the structure. Elk-2 penetrated the Puri Limestone below the gas-water contact. The Elk-4 well penetrated the Puri Limestone again, but at depth it intersected a gas-bearing reefal facies of shelfal limestone which was tested as a gas discovery. A thrust fault separates the Elk structure from a major feature to the south that was named Antelope. Seismic and regional analogy studies indicated that a significant reefal buildup occurs over the Antelope structure. Subsequently, wells Antelope-1 and -2 appraised the lateral extent of the field to the south with good reservoir quality to an approximate extent sufficient to realise that a substantial gas field had been discovered. InterOil applied for a Petroleum Retention Licence, which was designated PRL 15 on granting by the Minister on 10 November 2010.

After many bold attempts to devise a scheme of development consisting of mini-LNG trains, including floating offshore LNG trains and all manner of deals, InterOil decided to farm down its equity and introduce an experienced project champion from amongst world-class players. After much wrangling and corporate intrigue, including arbitration hearings between new equity participants, InterOil finally left the Elk-Antelope gas field and its future development to a joint venture comprised of Total (as operator) 61.3%, Oil Search 22.835%, ExxonMobil 36.45% and other parties 0.5%. Altogether, some 10 wells have penetrated the Elk-Antelope structure, and the area is covered by several generations of 2-D seismic data. Subsequently, Oil Search merged with Santos and, once the project licences are granted, the Government will most likely exercise its lawful option to take equity at cost, reducing each participant's equity proportionately to give the final project equity as: TotalEnergies 31.1%, ExxonMobil 28.7%, Santos 17.7% and the State 22.5%.

On this basis, TotalEnergies, as it is now called, has sought to develop the field for the supply of gas for liquefaction and export of a projected volume of 5.6 million tonnes per annum (mta). Quite how this will be achieved has varied over time, with initial plans being for two 2.8 mta LNG trains, though this has changed to four electric-driven 1 mta trains plus use of liquefaction ullage in the PNG LNG Project on a tariffed basis. TotalEnergies negotiated and renegotiated a Gas Agreement with the Government for the Papua LNG Project. Subsequently, they have submitted applications for a total of six petroleum licences, including a Petroleum Development Licence covering the field and associated Pipeline Licences and Petroleum Processing Facility Licences, in May 2023. Recently, TotalEnergies has indicated that final investment decision (FID) for the Papua LNG Project is planned for the first quarter of 2026. A period of four years’ construction should possibly enable first LNG delivery by 2029.

I have not dwelt on smaller gas discoveries or other less conceived or marginally economic schemes of petroleum development. Indeed, little exploration is taking place as there is already a queue for gas development. As the Nation’s public and petroleum sector infrastructure develops and grows, perhaps some access costs to petroliferous areas may diminish and with that, fields of smaller accumulations may become economically viable for exploration and subsequent development. In all petroleum provinces around the world, there are normally a few giant fields, several large fields and a myriad of smaller fields. Hopefully, it is these smaller fields that will promote the domestic utilisation of gas and prosperity of Papua New Guinea.

The Future

Clearly, gas field development for gas liquefaction and export as LNG has a seemingly viable and prosperous future. However, all stakeholders must be warned that such massive enterprises are not undertaken lightly and without due diligence and apprehension of the risks associated with them of all kinds. Tens of billions of US dollars are invested in the original exploration, appraisal of discovery, development planning and design, and the development of facilities. In operation, hundreds of millions of US dollars are required each year to keep the facilities in good repair and operating optimally and safely. The end result is the net value, which is shared one way or another, whether through typical tax/royalty licence systems or production sharing contracts between the Government and companies.

Expectations of stakeholders need to be taken care of most assiduously. Transparency of operations and a resulting well-informed Government and people will have a better understanding of what is happening. The companies need to have timely and appropriate approvals, transparent uses of local content, and report key statistics openly. The Government needs to make sure beneficiaries at the community level get and understand their petroleum benefits which are prescribed by law, and that the wider public understand the real contribution of these endeavours to the people and the economy.